You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘guest post’ category.

We are fortunate to have a guest post today from Robin Averbeck. Ms. Averbeck is a doctoral candidate working on the community action programs of the Lyndon Johnson administration, and has some insights appropriate to the current interest in Charles Murray’s new book and the idea of a culture of poverty. It’s always a privilege to work with a student whose research is interesting on its own terms and also engages current events in an intriguing way.

In the winter of 1963, the sociologist Charles Lebeaux argued that poverty, rather than merely a lack of money, was in fact the result of several complex, interrelated causes. “Poverty is not simply a matter of deficient income,” Lebeaux explained. “It involves a reinforcing pattern of restricted opportunities, deficient community services, abnormal social pressures and predators, and defensive adaptations. Increased income alone is not sufficient to overcome brutalization, social isolation and narrow aspiration.”1 Lebeaux’s article was originally published in the New Left journal New University Thought, but also appeared two years later in a collection of essays by liberal academics and intellectuals called Poverty in America. In the midst of Johnson’s War on Poverty, the argument that poverty was about more than money – or, as was sometimes argued, wasn’t even primarily about money – was common currency in both liberal and left-leaning circles.

Read the rest of this entry »

[Editor’s Note: Bob Reinhardt, a PhD candidate in our department, submitted this TDIH before the late unpleasantness on our campus. He then asked if I would hold off on posting for a bit. Well, a bit has passed, and it’s time to talk about smallpox. Really, though, when isn’t it the right time to talk about smallpox? Thanksgiving dinner, I suppose. Anyway, thanks, Bob, for doing this.]

23 November

On this day in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson declared all-out war on a universally despised enemy. The announcement didn’t concern Vietnam — Johnson had escalated that police action months before — nor poverty, against which the US had allegedly been fighting an “unconditional war.” This particular declaration targeted a different enemy, older and perhaps more loathsome than any ideological or socioeconomic affliction: smallpox. As the White House Press Release explained, the US Agency for International Development and the US Public Health Service (specifically, the Communicable Disease Center, now the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) had launched an ambitious campaign to eradicate smallpox (and control measles) in 18 West African countries.* That program would eventually lead to the first and only human-sponsored eradication of a disease, and would also demonstrate the possibilities — and limits — of liberal technocratic expertise.

This is a guest post by our friend andrew, over by the wayside. Many thanks!

(Image from W.H. Michael, The Declaration of Independence, Washington, 1904)

On this day in 1941, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were taken out of their exhibit cases at the Library of Congress, carefully wrapped in acid-free and neutral packing materials, and placed inside a bronze container designed especially to carry them. When the packing was complete, the “top of the container was screwed tight over a cork gasket and locked with padlocks on each side.”*

The documents remained in this state for the next few days, until the Attorney General ruled on December 26th that the Librarian of Congress could “without further authority from the Congress or the President take such action as he deems necessary for the proper protection and preservation of these documents.” At which point the library went back to work:

Under the constant surveillance of armed guards, the bronze container was removed to the Library’s carpenter shop, where it was sealed with wire and a lead seal, the seal bearing the block letters L C, and packed in rock wool in a heavy metal-bound box measuring forty by thirty-six inches, which, when loaded, weighed approximately one hundred and fifty pounds.

Along with other important documents like the Magna Carta and the Articles of Confederation, the Declaration and the Constitution were then taken to Union Station in an “armed and escorted truck,” where they were loaded into a compartment in a Pullman car on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Accompanying the documents were Chief Assistant Librarian Verner W. Clapp and some number of armed Secret Service agents.

The documents left D.C. in the evening and arrived in Louisville the next morning, where they were “met by four more Secret Service agents and a troop of the Thirteenth Armored Division, who preceded by a scout car and followed by a car carrying the agents and Mr. Clapp, convoyed the Army truck containing the materials” to the depository at Fort Knox. The documents were to be kept there until it was determined that they could once again be considered safe in Washington, D.C.

It was not the first time the Declaration and the Constitution had been moved because of war.

[Editor’s note: Our friend Michael Elliot sends along the following request for help. And yes, at some point I really should respond to the Wilentz essay linked below. You know what else I really should do? Post a review of Nixonland.]

Like any self-respecting parent, my main goal is to indoctrinate educate my children so that they can share my own nuanced take on the world. My second goal is to avoid having to read the insipid dreck that passes for children’s literature at bedtime. For these reasons, I’m looking to pick up some books that will shove my five-year-old down the path toward becoming an American historian. (After reading Sean Wilentz, God knows I don’t want him to become a literary scholar.) So, any recommendations on books about U.S. history for the kindergarten set?

For the record, I’ve recently tried out a couple of short picture-books on Lincoln. My son was intrigued, but unfortunately found the assassination “too sad.” As Ari says, “What self-respecting five-year-old wants to be depressed?” Ari mistakes me for a parent who values his kid’s self-respect above his own.

Commenter Charlieford wants to put this to the EotAW community.

Last week I read a blog entry by a friend slamming Obama for, among other things, being our TOTUS, “Teleprompter of the United States.” He was offended by Obama’s use of a script (apparently) during his televised tribute to Walter Cronkite. Like a lot of conservatives, he was quick to pile on the criticisms—the delivery was cold and emotionless, not “from the heart,” the speech may not even have been written by Obama, and it included “large words embedded into the speech to ensure that only half of the Americans who heard the speech would understand it.”

That last one didn’t sound at all right and I went back and re-listened to the speech. I didn’t notice anything egregiously arcane or overly sophisticated in his vocabulary. I asked the author what had offended him in that regard, and he didn’t have a convincing response. Initially I concluded that he had simply over-reached, but now I think he was really imputing, without realizing it, his general reaction to Obama’s presidential discourse to this particular speech.

What makes me think so is watching Obama’s impromptu address on Gates-gate, or, more specifically, his comments on his earlier intervention (“stupidly”) in the affair. It also gave me a theory on Obama’s tendency to rely on a teleprompter.

The Cronkite speech, which he does seem to be reading, is a humble piece of oratory. A middle-of-the-road, ultimately forgettable, presidential testimonial on an occasion of national grief. It’s forgettability is entirely appropriate, I think (I tend to cringe when the rhetoric gets too poetic, as with Reagan’s Challenger address, or anytime anyone speaks about ceremonies of innocence being drowned).

But look at his impromptu, unscripted, comments on Gates-gate, this past Friday, keeping in mind the above-mentioned blogger’s sensitivity to “large words.” In comments that took a little more than five minutes to deliver, Obama uses the following terms: ratcheting, calibrated, maligning, resolve, garnered, extrapolate, fraught, teachable-moment, portfolio.

I submit to you that some or all of these terms are on the periphery of, perhaps even entirely outside, the familiar universe of discourse of most self-proclaimed “ordinary” Americans. You know, the kind that live in West Virginia and environs. The kind that voted for Hillary Clinton in the primaries.

(I would also argue that the general tone of the comments—with its nuanced approach to the whole matter, self-aware and self-critical, calling on everyone involved, including himself, to step back, reflect, think deeper about it all—didn’t exactly embody the typical attitudes that class of Americans are attracted to, but that’s another discussion.)

What I’d like to hypothesize now is this: that Obama, alumnus of Columbia and Harvard, Obama the former professor of Constitutional law at the University of Chicago, above all, Obama the reader, lapses into a style of speaking that is susceptible to the criticism of being overly-sophisticated, even borderline incomprehensible, to ordinary Americans. And that he uses the teleprompter, not so he can deliver high-flying rhetoric, but so he can ratchet it down.1

We all have various ways of navigating these difficulties. Some of us simply give up reaching the ordinary folk. We find ourselves, deliberately or by accident, moving almost entirely in circles made up of educated people. Our exchanges with the ordinary folk occur primarily in the vicinity of a cash-register. Politicians don’t have that luxury. Some, particularly those from the South, have an almost preternatural ability to slip back and forth between discourses, from the vulgate to educated-ese with barely a hiccup, depending on the audience. Obama’s strategy, I’m guessing, is to write out what he wants to say, which allows him to calibrate his language, uh, more felicitously.

1Nice, Charlie—ed.

[Editor’s Note: When Jacob Remes isn’t using his superpowers to fight crime, he toils as a PhD candidate in history at Duke University, where he’s writing a dissertation about the Salem Fire and the Halifax explosion. You can find more information here. And if you’d like to write a TDIH, please let me know.]

The workers at Korn Leather Company in Salem, Mass., made embossed patent leather by coating leather with a solution made of scrap celluloid film, alcohol, and amyl-acetate, and then applying steam heat. On this day in 1914, at about 1:30 in the afternoon, something went terribly wrong, and—perhaps not surprisingly given the flammable nature of the work—the whole rickety structure caught fire. Half an hour later, the fire had spread to fifteen more buildings, forcing 300 workers to flee. By 7:00 that evening, the fire crossed into the Point, a tightly packed neighborhood of three- and four-story tenements, filled with the immigrants who worked at Salem’s leather factories and the enormous Naumkeag Steam Cotton Company.

The Salem Evening News reported:

The rush of the flames through the Point district was the wildest of the conflagration, the flames leaping from house to house with incredible rapidity. Police officers and citizens went from house to house in the district when it was seen that it must fall a prey to the flames, warning the occupants to get out and get out as quickly as possible. Soon the streets were thronged with men, women and children, carrying in their arms all they could of their belongings, while wagons, push carts and now and then an automobile were pressed into service in the removal of goods.

The fire burned through the night, and by the time the fire reached the Naumkeag cotton mill, it was too hot; although the factory was equipped with modern devices to stop fires, it burned down, leaving 3,000 people without jobs. All told, the fire destroyed 3,150 houses and 50 factories and left 18,380 individuals homeless, jobless, or both. Of these people, nearly half were French-Canadian, the group that dominated the Point. “St. Joseph’s structure is not only destroyed, but the whole parish has been scattered to the winds,” the Salem Evening News wrote that week of the neighborhood’s French-Canadian parish. Many camped for weeks at nearby Forest River Park, under the watchful eye and armed authority of the National Guard.

Fires were endemic to 19th-century industrial cities. Just in the 35 years preceding the Salem Fire, Chicago (1871), Boston (1872), Seattle (1889), St. John’s, Nfld. (1892), Hull and Ottawa (1900), Jacksonville, Fla. (1901), Toronto (1904), Baltimore (1904), and San Francisco (1906), and Chelsea, Mass. (1908), among others, all suffered major conflagrations. But changes in building and firefighting meant that in the twentieth century, large-scale urban fires declined drastically. Automobiles required clear roadways, so the flammable material that used to often sit in streets, blocking fire engines and spreading fires, was gradually removed. Progressive building codes—like one proposed and rejected in Salem in 1910 that would have required noncombustible roofs—and ever-more professionalized fire-fighting helped too. If the Salem Fire was not the last of its kind, it was among the last. That at most six people died in Salem is testament to the strides made in preventing, containing and fighting fires, even when fire departments could not ultimately save property. In 1951, the National Fire Protection Association published a list of major conflagrations in the first half of the twentieth century. After 1914, only one urban fire came close to Salem’s in the number of buildings burned or the estimated dollar amount of damages: a fire in Astoria, Oregon, in 1922 that destroyed 30 city blocks and caused $10 million in damages.

Yet the decline of industrial conflagrations did not, of course, spell the end to urban disasters. Three and a half years after the Salem Fire, a ship explosion destroyed about a quarter of Halifax, N.S., killing around 2,000 people. The Halifax Explosion was an accident, but it heralded the urban destructions of the 20th century. All sides of the Second World War unleashed massive, unprecedented on cities. Geographer Ken Hewitt estimates that strategic bombing destroyed 39% of Germany’s total urban area and an astounding 50% of Japan’s. Neither these statistics nor the equally startling numbers of dead and bombed out (60,595 dead and 750,000 homeless in the U.K., 550,000 and 7,500,000, respectively in Germany, and 500,000 and 8,300,000 in Japan) adequately convey the destruction of families, communities, and institutions that came with these urban destructions. Twentieth century wars, their technology and ideology created a special brand of horror, which made their urban destructions starkly different from the industrial fires of the 19th century. When urban civilians became common targets, cities were made military symbols. It is not for nothing that terrorists have twice targeted the World Trade Center, a symbol of American urban might and culture.

If urban destruction in the 19th century was largely a result of industrial accidents and the destructions of the 20th century were from war, the 21st century may be a period of meteorological and seismological disasters. While there remains scientific disagreement about the effect of climate change on the frequency and intensity of hurricanes, there is mounting evidence that global warming has contributed to a greater proportion of storms being particularly bad. Global warming also contributes to other meteorological disasters, like floods, heat-waves, and droughts. Moreover, the chronic effects of global warming, especially coastal erosion, means that cities are less able to withstand extreme storms and floods. This means that cities will be more susceptible to destruction stemming from events that global warming will not increase, like tsunamis. There is some evidence, too, that even on land seismological disasters will likely become worse this century, since urbanization—especially the growth of shanties and slums in global megacities—leads to more death and destruction when earthquakes strike. As always, the social effects of these “natural” disasters are felt most by the poor, both globally and within developed countries.

Louis Warren once again helps us understand the historical roots of California’s current crisis. Thanks, Louis.

California’s crisis is such that the number one manufacturing and farming state is unable to sell its bonds. As I explained in my last post, this condition stems in part from constitutional requirements of the supermajority.

Some commentators on the right prefer a different explanation. This is the useful canard that California is congenitally left, and that liberal policies lead inevitably to financial collapse.

To be sure, the left is not blameless in this debacle. But much of California’s political upheaval of the last decade and a half has been driven by the collapse of the state’s once-formidable Republican Party. Alarmingly, national Republicans now seem to follow their lead. Progressives may think this cause for celebration – – but if the Republican Party in the U.S. becomes what it is in California, America has some hard days ahead. Read the rest of this entry »

[Editor’s note: Louis Warren, our colleague and friend, returns to write about why you should care that California has decided to self immolate.]

[Editor’s note II: This post has been updated to reflect author’s changes.]

While the scolding and the tut-tutting goes viral — “California, such a shame those weird, flaky people can’t live within their means” — it’s time for some serious reflection about how the nation’s richest, most populous state got where it is. California, home to one in eight Americans, has a GDP bigger than Canada’s. And it’s in the middle of an on-going fiscal calamity which threatens to rip our legislature apart (again). This week, the governor went to the White House to beg for federal backing of state bonds, a move which threatens to make California’s predicament a national drama.

So, whatever the solutions to California’s problems, rest assured those problems are coming soon to a theater near you, because unlike any other place, the Golden State is where the future is now. In a sense, California is the un-Las Vegas. What happens here does not stay here, it goes global. The growth of independent political voters? Auto emission regulations? The tax revolt and modern conservatism? We saw them all first in LA and San Francisco. Watts erupted in flames before any other American ghetto in the 1960s. Harvey Milk led the charge for gay rights on our televisions first. The tech boom was here first. And so was the bust.

So what explains California’s budget crisis, and what can we learn from it? In truth, the reason California has been unable to balance its budget has little to do with being an outlier, and more to do with some small, structural peculiarities that simply don’t suit a modern American state. Our politicians are about as partisan as Americans in general (read “very”). Our state tax rate is marginally higher than most others (but it is not the highest), and the level of our spending on public education and other services is also somewhat higher. So what gives?

The root of our problem is our state constitution, which requires a two-thirds majority to raise taxes or pass a budget. In some ways, this is peculiar. No other state requires two-thirds majorities to perform those two vital functions (although Rhode Island and Arkansas both require 66% to raise taxes, their budgets pass on simple majority votes). In other words, to pass a budget every year in California requires the same level of amity and consensus other states require for a constitutional amendment.

Where did the supermajority originate? Although many blame Proposition 13 (passed in 1978), California’s constitution has in fact been tilted this way for a very long time. The state first passed a constitutional amendment requiring two-thirds majorities to approve budgets back in 1933. The rule kicked in only when budgets increased by 5% or more over a previous year. But since most budgets did increase by at least that much (California was growing by leaps and bounds), it kicked in a lot.

Even then, budgets passed with little trouble. California Republicans fought to restrain expenditures, then voted to raise taxes to cover what the budget required. Democrats fought for public education (including the nation’s most extensive system of higher education). In the 1950s and ‘60s, California took on more debt than any state in history to fund massive public works, including highways, university campuses, and the state aqueduct system (which together did much to create the wonders of LA and San Diego as we know them).

All this spending was funded by taxes and bonds, which voters approved at the ballot box. This despite the fact that in 1962, voters and legislators united to “streamline” the budget process and require two-thirds majorities for ALL state budgets. Still, Republicans and Democrats typically hammered out deals, with Republicans voting for taxes only after exacting concessions from Democrats.

So it went for another decade or so, when the rise of movement conservatism changed the terms of debate. Republicans never liked taxes, but they saw them as an unfortunate necessity. By the 1970s, conservatives increasingly sounded like the leader of California’s tax rebellion, Howard Jarvis, who condemned all taxes as “felony grand theft.” With passage of his Proposition 13, voters mandated that all tax increases required two-thirds majorities, just like state budgets.

Still, for many years, leading Republicans could contain their most conservative brethren and hammer out deals in the old-fashioned way. As late as 1991, a Republican governor (Pete Wilson) championed a tax increase and budget cuts to close a deficit. In 1994 he won re-election.

But already the tide was turning. As Wilson discovered during his abortive presidential campaign in 1995, the “No New Taxes Pledge” had become a litmus test which he had failed. This hostility to all taxes is now conservatism’s defining feature. It is also, historically speaking, quite new. More than anything else, this is what killed the consensus that drove California’s 66% majorities.

The proof is in the pudding. The state has had the same supermajority requirements for budgets for the last 47 years. But only for about the last two decades has the budget become a source of continual drama, with legislators deadlocking 18 years out of the last 22. There has been chronic division in the last ten. We are a long way from the consensus that built the Golden State.

But it’s worth observing that we’re not beyond consensus. Today, California’s state assembly is less than 40% Republican, a situation that is not likely to change much in favor of Republicans (for reasons I’ll discuss in a later post). They are stalwarts for tax cuts, but over 60% of the state’s voters have opted for higher taxes and more public services. In any other state, this wouldn’t even be an argument. But in California, it’s a crisis because of the supermajority amendment to the constitution. The state is not “dysfunctional.” It’s not “flaky.” But the constitution no longer suits political realities, and it seems bound for some kind of change. The Bay Area Council, a group of prominent San Francisco business leaders, has proposed a state constitutional convention to require only a simple majority for new budgets and taxes. Their idea appears to be gaining ground.

This all might seem a peculiar California story, but to any observant American it is a sign of the times, a symptom of the country’s divisions. The U.S. Congress has no supermajority requirement, but California’s travail is echoed in the Senate, where rules require 60 votes to end a filibuster. Democrats now control 59 seats, Republicans have 40. The empty seat is Minnesota’s, where Democrat Al Franken appears to have eked out a victory over Republican Norm Coleman in the 2008 election. That was six months ago. Since then, Republican operatives have poured money into legal appeals, tying up the business of the country, stalling health care reform, threatening a filibuster of the president’s Supreme Court nominee and many other big initiatives, to buy their flagging party some time. From the Pacific to Minnesota to the nation’s capital, California blazes a path into the future — like it or not.

[Editor’s note: Seth Masket, a good friend from my days at the University of Denver, has a new book out. He also has this post, about California’s budget politics, for us. Thanks, Seth, for doing this.]

During a difficult economic year in which the state faced a severe budget shortfall, California’s Republican governor worked with Democratic leaders in the state legislature to craft a budget that contained a mixture of tax increases and service cuts. The Republican party stood together on the vote, with the exception of one holdout in the Senate.

Sound familiar? Actually, the year was 1967. Many of the story’s details are familiar because they recur from time to time in California. The real difference, though is the fate of the Republican state senator who refused to vote with his party. Instead of being driven out of politics, John Schmitz was renominated by the Republicans and reelected by his Orange County district the following year. Also, all the other Republicans in the state Senate voted for the budget. Schmitz refused go along with the tax increases that the rest of the Republicans in the senate, and Governor Ronald Reagan, found acceptable.

The situation in California is notably different today. The state legislature still requires a two-thirds vote in both houses to pass budgets, but that rubicon has proven steadily more difficult to cross. Virtually all Republicans will oppose any tax increase; any Republican willing to cross party lines and vote for a Democratic tax will find himself out of work before the next election. This happened after the 2003 budget stalemate; four Republican Assemblymen were dispatched to private life because of their votes in favor of Governor Gray Davis’ tax hike. Notably, none were dispatched in the next general election. None made it that far. Most faced difficult primary challenges from their own party and either lost or decided to retire.

The same thing happened earlier this year when Democratic legislative leaders worked with Gov. Schwarzenegger to produce a compromise package of service cuts and tax increases. The Democrats once again found a few Republicans to cross party lines, and once again those Republicans are being purged from the party. The state party has cut off funds for the six apostates, each of whom now faces a recall petition.

The treatment of these lawmakers sends an unmistakable signal to future lawmakers who would consider crossing party lines: the wrong vote will be your last.

One could blame any of California’s political peculiarities — the two-thirds budget rule, initiatives that have placed much of the budget off limits, term limits, etc. — for the budget stalemates, but the fact is that they wouldn’t occur if the parties were less disciplined. Note what has happened in the parties over the past sixty years. The figure below charts the mean DW-NOMINATE score, which is a measure of roll call liberalism/conservatism, for Democrats and Republicans in the state Assembly:

|

The parties have moved farther apart, with the Republicans becoming more conservative and the Democrats steadily more liberal. Compromise, which is usually necessary when passing a budget by a two-thirds margin, becomes almost impossible in this environment.

Why are the parties moving apart? (Self-promotion coming.) This is something I explore in my new book. Part of it can be explained by national ideological trends. But part of it is a function of who is running the parties.

California’s political parties are run at the most local level by informal networks of activists, donors, and a few key officeholders. These people work together to pick candidates they like and provide those candidates with endorsements, money, and expertise that can put them over the top in the next primary election, and they deny other candidates these same resources. Because these actors are relatively ideologically extreme, so are the candidates they select. If a politician they put in office strays too far from the principles they hold dear, they can deprive that politician of her job by withholding funding, by running a more principled challenger in the next primary, or, in the most extreme cases, by organizing a recall.

This informal style of organizing parties is not unique to California but fits particularly well there because of state rules limiting the formal parties’ participation in politics. As the informal parties have grown more organized, largely since the 1960s, the legislative parties have moved further apart. While there are still plenty of moderate legislative districts in the state, there are almost no state legislators who could accurately be described as moderate; the penalty for moderation is too high.

Should Californians reject Proposition 1A on May 19th, we’ll no doubt see another round of budget negotiations in the legislature. These will be made difficult by the party operatives on the right (who will punish any Republican who votes for a tax increase) and the party operatives on the left (who will punish any Democrat who votes to eviscerate key social programs). Partisanship makes legislative progress much more challenging, particularly during times of divided government. This is the reason the state keeps coming up with short term methods of financing its deficits and kicking them down the field for a few more years rather than actually addressing its budget shortfalls — given the political climate, it has no other choice.

This is certainly not to suggest that parties are the cause of California’s problems. The state more or less tried bipartisanship in the early 20th century. The result? Corruption. But while strong parties can keep a tab on corruption, they carry their own burdens. They aren’t necessarily the problem, but they can make other problems worse.

[Editor’s note: Michael Elliot returns! Thanks, Michael, doing this.]

While I was a graduate student, I went to a meeting during which the Director of Graduate Studies was asked about the department’s “placement rate.” The DGS wanted to emphasize the positive, and so he stated that it was nearly one hundred percent: Everyone who had kept looking for a tenure-track position and not given up, he said, eventually found one.

Even I could see the fallacy of the argument: after two or three or four tries at landing a tenure-track professorship, most PhDs will find other kinds of paying work because, well, they need to be paid. (I didn’t bother to ask how such a badly managed department was actually keeping records to document this miraculous job placement.) I thought about this exchange when, in response to Mark Taylor’s antiestablishment polemic, Sunday’s New York Times published this letter:

Doctoral programs that fail to place their graduates in research positions should not respond by attempting to become M.B.A. or M.P.A. programs. Instead, they would better serve their prospective students by setting the right expectations through full disclosure of their recent graduate placement history. With this information, applicants could make informed decisions when choosing a graduate school.

I share the desire for transparency, and I probably would have said the same thing when I was a graduate student. But I am increasingly wary of focusing too much on “the placement rate” as the magic number that will make comparison shopping possible.

To start, “placement” turns out to be harder to measure than you might think. Most people, when talking about humanities, mean it to be the percentage of people who seek tenure-track jobs and find them. But what exactly does that mean? What about those people who seek tenure-track employment but limit their search to a handful of cities — do they get included? What about the people who land a job, but only after traveling the country for years on one-year temporary contracts? Is it the number of people who get a job in any given year? Or, as my old DGS claimed, the percentage of people who eventually get them?

At a pragmatic level, until there’s some shared definition of what “placement history” means, prospective doctoral students should be wary of putting too much stock in the information that they receive. The fact is that a substantial number of PhD’s will never conduct a national search for a tenure-track position. In my program, I often see graduating classes in which the majority are pursuing other options, including other forms of academic work, temporary teaching positions (that allow them to choose their geographic location), and jobs outside the academy. Our current DGS calculated recently that just over 60 percent of our graduates in the last five years are in tenure-track jobs. That is actually higher than I expected — and much higher than was true of my own graduate program when I was there — but it is hardly a “placement rate.”

This is not to say that we shouldn’t keep pressing for disclosure about employment. And I think everyone who teaches in a PhD program should be forced to consider carefully the employment of its graduates. But we should be careful about what we are asking for. First, forget the term “placement.” No one gets placed any more. (Maybe they never did.) PhDs get hired for jobs that they have earned. Second, it’s crucial to ask what percentage of graduates end up teaching in the academy, what percentage of those are on the tenure-track, and what other kinds of positions graduates hold.

Finally, graduate programs should calculate the average time that it takes those who seek tenure-track positions to secure them. (The national average is that it takes just over ten years from the time that a student enters graduate study.) Programs should then ask what kind of financial resources — including temporary teaching employment — their universities can provide to cover that whole duration, including the period that extends beyond when the students actually receive their degrees. Those programs that cannot identify adequate resources to cover that full spread of time should take a hard look at themselves.

[Editor’s note: Karl Jacoby’s Shadows at Dawn: A Borderlands Massacre and the Violence of History is a must read. And the website he created to support the book is a model for the future. Below, he shares some thoughts on what that future might look like. Thanks, Karl.]

As the American newspaper industry collapses around us, its economics imploding under pressure from the worldwide web, we can begin to see hints that the book publishing industry is on the cusp of the same downward spiral. History book sales are down. Penguin and other presses have announced layoffs. The once venerable Houghton Mifflin may soon cease to publish trade books altogether.

Such changes ought to be sobering to historians. Ever since history first emerged as an academic profession in the mid-nineteenth century, the basic unit of production has been the book. One needs to publish a book to get tenure and, at most institutions, publish another book to get promoted to full professor. What will happen to this century-old tradition if books become harder to publish and more historical scholarship heads off for the new, untamed frontier of the web?

Like everyone else in publishing and academia, I don’t have a complete answer to this question. But based on my recent experience — publishing a book in the Penguin History of American Life series (Shadows at Dawn: A Borderlands Massacre and the Violence of History) and creating a companion website — I have gathered a few random insights, which I offer below in the hope of beginning a long overdue conversation among historians about the perils and possibilities before us.

[Editor’s note: Our good friend, awc, elaborating on this comment, sends along the following from the far eastern edge of the American West. Thanks, awc.]

Politico’s recent feature on Amity Shlaes’ The Forgotten Man is an example of one of my pet peeves: the evaluation of economic policy in terms of statistical factors like growth, the stock market, and unemployment rather than systemic qualities like equality. The piece discusses the popularity of the book among D.C. conservatives, briefing mentioning Professors Rauchway and Krugman, who have skillfully defended the efficacy of New Deal recovery policies. When Shlaes responds that she intended the book to question the ethics of the New Deal, not just its utility, Politico simply drops the pretense of debate. They ask neither scholars nor ordinary folks to evaluate her celebration of the poor beleaguered corporation. The result is an article that presumes that New Deal laws can be defended only as spurs to recovery, not as devices for promoting a better society.

This narrowly economic approach is worse than conservative; it’s ahistorical. New Deal staffers cared about raising wages, protecting workers, ending poverty, conservation, recreation, and a hundred other things aside from recovery. They didn’t view themselves as failures when the jobless rate rose. And while Republicans made significant gains in the 1938 elections, the overwhelming majority of Americans still endorsed the Roosevelt administration. Then and now, policy isn’t solely about GDP per capita.

The journalistic focus on utility is also phony. The press is fixating on a technical question, namely the effectiveness of government stimulus. While this discussion is inevitable, the Republican affection for Keynesian tax cuts suggests the real disagreement is moral. Today, historians usually defend the New Deal not just because it helped end the Great Depression, but also because it relieved human misery, promoted social equality, and strengthened the nation for its confrontations with Nazism and then Communism. Shlaes disagrees, and to her credit, she wants to have this argument. But journalists keep pulling the debate back to the unemployment numbers. They’re just looking for a policy that will return us to the status quo ante.

|

[Editor’s Note: Adam Arenson (bio below), a friend and occasional commenter here, has graciously provided us with a guest post. Thanks, Adam, for doing this.]

Quick: What does your bank look like?

I admit it; I don’t know either. There are glassed-in tellers. There’s a metallic sheen off the ATMs. Some peppy posters promoting savings plans for dream retirements. But it all adds up to a rather anonymous décor. More than once the names and the colors have changed, and I hardly noticed.

|

But there are banks I remember. Growing up in San Diego, I recall the grand lobbies of the Home Savings banks, some with gurgling fountains and sculptures. They had parking lots, and wide arches framed the entrances. Most spectacular were the mosaics: thousands of little tiles arranged to show carefree beach scenes, vaqueros from the Californio past, Victorian ladies in their bonnets, Chinese miners and Franciscan friars. Going to the bank was a history lesson and a celebration of California identity; it was a civic space, a place to linger, a landmark for a child who hardly knew pennies from dimes.

|

Home Savings of America is no more; in 1998, the bank was purchased by Washington Mutual, which last year was seized by the federal government and sold to Chase. Though the Washington Mutual name has lingered, it too is gone: this month, its depositors are receiving Chase ATM cards, and, on the East Coast, Washington Mutual branches are being closed and sold off.

In this moment of financial turmoil, however, we as Californians should ask that the cultural assets of the bank be preserved. These mosaics, paintings, and stained glass artwork are a unique California treasure deserving protection.

|

This art is the legacy of Millard Sheets. For most of his career, Sheets (1907-1989) served as director of the Otis Art Institute (now the Otis College of Art and Design), where the library is now named in his honor. Beginning in 1952, Sheets, Susan Hertel, and Denis O’Connor spent three decades designing Home Savings banks and providing them with memorable art: In the Lombard branch in San Francisco, a mural provides a timeline of local history from Native Americans to the Golden Gate Bridge; at the Pacific Beach branch in San Diego, mosaics of Spanish missionaries and soldiers stand guard; in Studio City, images of vaqueros over the door are joined by prospectors and movie directors. Sheets completed commissions for the Mayo Clinic, the Honolulu Hilton, and Notre Dame University, yet his masterpieces are here in southern California, and they have been left vulnerable.

After the sell-off of Home Savings branches in the late 1990s, Sheets’s mosaics have come to grace a barbeque-grill vendor in La Mesa, California, and a mattress store on Santa Monica Boulevard in Los Angeles. Are the landlords cognizant of their significance, and to renters maintain and repair them? The fifty-foot-tall mosaics on the marquee banks are probably safe, but what about the small, two-by three-foot panels of life on the sea floor, or the delicate paintings of palomino horses?

|

This artwork is vernacular, with humble materials and few pretensions. Yet it is still worthy of preservation and care, an important public treasure alongside the holdings of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art or the Getty Museum.

We must look out for these mosaics, these paintings and stained glass, especially when their current owners—banks and real-estate developers—are desperate to liquidate assets and regain their footing. I’ve begun compiling an inventory of this artwork online and welcome additions from readers. Those concerned might also contact their local preservation board to ask that this artwork receive landmark protection, or perhaps arrange transfer to a local arts council or museum.

During these days when Californians have come to associate their banks only with bad news, we have an opportunity to preserve some of them as unique chronicles of our local history. Future generations will thank us for recognizing that, sometimes, a bank’s most precious asset is the bank building itself.

Originally from San Diego, Adam Arenson is an assistant professor at the University of Texas at El Paso, where he teaches nineteenth-century North American history, with a particular interest in the American West and its borderlands. He has published articles on Ansel Adams photography, library furniture, and more, and is co-blogger at makinghistorypodcast. He is working on a book manuscript,The Cultural Civil War: St. Louis and the Failures of Manifest Destiny, and co-editing a volume on frontier cities; more information here].

[Editor’s Note: Professor Lori Clune returns today for another guest post here at EotAW. Thanks, Lori, for your help with this.]

On this night in 1953, 71.7% of American televisions were tuned to CBS as Ricky and Lucy gave birth to their son, Little Ricky, on I Love Lucy. Well, actually Lucy did all the work off-screen. As many of us recall (thanks to endless reruns) Ricky spent much of the episode in outrageous voodoo face makeup for a show at his club, the Tropicana. From Lucy’s calm statement, “Ricky, this is it,” to the nurse holding up the swaddled bundle, the viewer saw no drugs, pain, or mess. Heck, we weren’t even sure how Lucy came to be “expecting” (CBS nixed saying “pregnant”), what with their two twin beds and all. Lucy and Ricky Ricardo (Lucille Ball and Desi Arnez) — also married in real life — had welcomed their second child, also a boy, via scheduled caesarian section that morning.

The next day 67.7% of televisions tuned in to watch Dwight D. Eisenhower take the oath of office as the 34th POTUS. During the 1950s, television was invading American homes. Only 1 in 10 American homes had a television in 1949; by 1959 it was 9 in 10. Eisenhower’s inauguration (while earning a lower rating than Little Ricky’s birth) reached a substantial number of Americans, about seven times more than had seen or heard Truman’s inaugural just four years before.

As Eisenhower explained in his inaugural address, in 1953 the United States faced “forces of evil…as rarely before in history.” No one needed to be told that the forces of evil were communist. Few Americans, however, could have imagined that a force of evil was the very red-head they loved in their living rooms.

Just eight months after the birth of Lucy’s “sons,” the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) charged Lucille Ball with membership in the Communist Party. Ball had registered with the CP in Los Angeles in the 1930s. She may have even held some meetings at her house. Ball testified to HUAC that she only joined the CP to placate her socialist grandfather who had insisted that she register as a communist. She claimed to be ignorant and “never politically minded.” When pressured by the press, her husband Desi Arnez retorted, “the only thing that is red about this kid is her hair – and even that is not legitimately red.”

Within days of her testimony, HUAC took the unprecedented action of calling a press conference and announcing that “there is no shred of evidence” linking Lucille Ball to the Communist Party. The committee made this unusual “public exculpation” because they wanted to, in their words, “insure that distortion of available facts not be permitted and that rumor not be substituted for truth in any case.” Historians argue that pressure from CBS and I Love Lucy sponsors – particularly Philip Morris – inspired HUAC’s action. Regardless of the reason, after a “seven-day brush with the blacklist,” HUAC cleared Lucille Ball’s name. Few accused communists were so lucky.

President Eisenhower enjoyed remarkable approval ratings, averaging over 60%, throughout his eight years in office. However, based on TV ratings, Americans loved Lucy more. In fact, Americans loved Lucy so much, they were willing to forgive her purported membership in the Communist Party. Desi Arnez explained, “Lucille is 100 per cent an American…as American as Ike Eisenhower.”

Some 50 million Americans watched Lucy during the 1953-54 season. Everyone still loved Lucy. A lot.

(This isn’t a guest post by nobody’s friend, Ben Shaprio. This is just a tribute. Via S, N!)

I first got into HBO’s hit television program The Wired about two years ago. A stranger mentioned it to the person in front of him at the 700 Club cafeteria, and by the time I finished the first episode, I knew I would be telling people I was completely hooked. (This, by the way, is my Recruitment Rule for The Wired: watch the first four minutes. If you don’t like it by then, dump out.) I am so excited by my enthusiasm for the show, in fact, that I often tout the first episode of The Wired as the best show in the history of television. I don’t simply love this episode for its terrific acting, wonderful writing, quirkly plotting, or mind-boggling twists. I also love it because of its subtle conservatism. Here are the top five conservative characters on the first episode of The Wired. Beware—SPOILERS INCLUDED.

1. William Rawls: John Doman’s tough Homicide investigator, William Rawls, is the top conservative character on television, bar none. Rawls is a real man’s man, a true paragon of conservative integrity. He knows that America is a meritocracy and, according to Wikipedia, in Season 4 openly attacks the reverse racism of affirmative action by proving that, instead of working up the ranks honestly like he has, the blacks in the Baltimore Police Department were recruited up the chain of command because of the color of their skin. This racism created a leadership vacuum, and like true conservatives, Rawls knows the value of a true leader of men. He may not always love the men beneath him, but he knows they need discipline and is determined to give it to them.

2. Jimmy McNulty: If every public servant showed McNulty’s commitment to civic duty, we would never have heard the odious phrase “President-Elect Obama” said without a snigger. In this episode alone, McNulty attends a trial when he could have been at home and stays up all night to make sure his report is on his deputy’s desk at 0800 clean and with no typos. Here he is in a clip from Season 2, going above and beyond the call of duty:

He’s also a family man who wants nothing more than the judge to give him more than three out of four weekends with his children.

3. Snot Boogie: Every Friday night, anonymous young black men would roll bones behind the Cut Rate, and every Friday night, Snot Boogie would wait until there was cash on the ground, grab it, and run away. Snot Boogie knew these games were unsanctioned and bravely confiscated the illegal proceeds even though he knew the young black men would catch him and beat his ass. To do what you know to be right, no matter the consequence, is a true conservative value.

4. The Anonymous Young Black Men behind the Cut Rate: The anonymous young black men behind the Cut Rate are American icons. They let Snot Boogie in the game even though he always stole the money because “[i]t’s America, man.” But it’s not liberal America, man, as should be obvious both by their devotion to the idea that while this is a free country, all decisions have consequences, and their commitment to capital punishment. They could have just whooped Snot Boogie’s ass like they always whoop his ass, but the anonymous young black men behind the Cut Rate know how to prevent the next generation of Snot Boogies from repeating the mistakes of the previous.

5. Avon Barksdale and Stringer Bell: I cheated here, but this is a Top 5, not a Top 6. Avon and Stringer are pure capitalists, compassionate but tough. Avon is a family man. When his cousin D’Angelo comes to him asking for a job, Avon and Stringer decide to give him one. But both men know there’s no such thing as a free lunch, so they also decide to teach D’Angelo that, in America, hard work is its own reward. Everyone has to start in the pit, but with a little hard work, anyone can end up running a tower.

The first episode of The Wired is a show chock-full of conservative values. It mentions God and quotes the Bible on a regular basis. It debates police vs. criminals and free enterprise vs. socialism. It promotes the value of the nuclear family—virtually every character on the show has dealt with a broken home, and they all pay the price for it. But everyone should know that the first episode of The Wired is one of the most conservative shows on TV. That’s part of what makes it so juicy.

(x-posted.)

[Editor’s note: silbey’s back for another guest post. Which reminds me, there are only sixteen shopping days until Christmas and thirteen until Hanukkah. Hey, you know what makes a great gift? A beautifully written, deeply researched, and thoughtfully argued book, that’s what. Anyway, thanks, silbey, for your efforts.]

On this day in history (Tokyo time), units of the Imperial Japanese Navy mounted an assault on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor. English language accounts of the attack, whether scholarly or popular, have focused on the American side of things, usually with a nod to Japanese treachery. But it is the Japanese side that is actually—in military terms—the more interesting. Like the Germans in 1940, the Japanese showed with devastating effect the value of a new method of warfare. The attack on Pearl Harbor rewrote the doctrine on naval warfare, and much of the next three years consisted of both navies, Japanese and American, desperately deciphering the writing.

What was revolutionary was not the use of airpower. Or, to put it more accurately, it was not simply the use of airpower. Aircraft carriers had appeared in all the world’s navies in the interwar period and were now integral parts of the fleet. The short-ranged and slow planes flying off an aircraft carrier were, however, largely incapable of inflicting substantial damage on the main line of a battle fleet, Billy Mitchell, notwithstanding. Against the enormously thick armor of the battleships—designed to protect against shells coming in at supersonic speeds—the puny bombs carried by those aircraft did little damage. Thus, the aircraft carrier became an adjunct to the heavies, used for scouting and observation. The battle line charged forward while the aircraft carrier lurked in the background, a second-class citizen.

What changed in the run up to WWII was the pace of technological innovation and doctrinal experimentation. The basics of the aircraft carrier had been settled in the 1920s and remained similar throughout the war, changing only in size. But planes evolved rapidly and dramatically in the 1930s, a pace that accelerated in the late 1930s. Aircraft went from being slow short-ranged biplanes to fast long-ranged mono-wings. Plane generations shifted from year to year, and an aircraft that was cutting-edge one year might be obsolescent the next. The two navies which took the greatest advantage of this were the American and Japanese. Both, surrounded by massive oceans, had a vested interest in naval excellence, and both worked feverishly to figure out how to use these new weapons.

As a result, doctrine sped along with technology. The challenge was to deliver massive amounts of ordnance at extended range against armored, maneuvering ships which, annoyingly, would shoot back. The settled result in both navies was the creation of three kinds of aircraft: dive-bombers, torpedo planes, and fighter escorts. The first, dive-bombers, would attack from high in the sky, diving towards the target and releasing the bomb at the last moment before pulling up. Torpedo planes, on the other hand, would attack from low, angling towards their target and releasing a torpedo which would drive the rest of the way in and hit the ship. Fighter escorts would protect the first two groups on their way to the target and as they attacked.

That was the theory. In practice, it proved enormously difficult for either dive bombers or torpedo planes to find or hit their targets. The Pacific was a big ocean and fleets—no matter how large—were an infinitesimal part of it. Even if found, warships did not *want* to be hit, and did everything they could to avoid it. They shot at the planes. They twisted and turned to avoid the bombs and torpedoes. They launched fighters to counterattack. They sailed into rain squalls. They kept their lights off at night. All of these things meant that the attacking aircraft usually scored an extremely low percentage of hits. Later in the war, at Midway, American planes mounted hundreds of attacks on the Japanese fleet and scored fewer than ten direct hits (all bombs, no torpedos). And Midway was an overwhelming American triumph.

In planes and aerial doctrine, then, both the Japanese and American Navies were similar. Neither had an enormous advantage in plane technology overall. The Japanese torpedo bombers, the Nakajima B5N (“Kate” its US identifier) was better than the American Douglas TBD Devastator. The torpedo it dropped was *much* better. The American Douglas SBD Dauntless was a better plane than its Japanese counterpart, the Aichi D3A (“Val”). The fighter escorts on each side were so different as to be nearly incomparable. The Japanese Mitsubishi A6M (“Zeke”, though better known as the “Zero”) was a lightweight, highly maneuverable, long ranged fighter plane that achieved those qualities by sacrificing any armor protection at all, either for pilot or plane. The American Grumman F4F Wildcat was not particularly maneuverable, rather short-ranged, and pretty heavy, but its toughness and heavy armament were legendary. Whereas Zeros tended to dissolve into flames under fire, the stories of Wildcats making it home after being hit by hundreds or thousands of bullets are too many to recount.

Where the Japanese surpassed the Americans was not in their use of the planes but in their use of carriers. Whereas American carriers were deployed singly, as part of a larger squadron including battleships, the Japanese put their carriers together—for the most important missions—as a single large striking force. Early in 1941, Admiral Isoruoku [ed.- dana]Yamamoto, the commander-in-chief of the Japanese Navy, organized the First Air Fleet, consisting of all of Japan’s carriers. The First Air Fleet, and most particularly the six heavy carriers composing the Kido Butai, or “Mobile Striking Force”, would be the hammer of the fleet. Off their decks could fly more than 300 warplanes, a larger number than that of any other fleet in the world. What they could not achieve in individual accuracy, the Japanese aimed to make up in numbers.

It was this fleet that sailed to attack Pearl Harbor. A British attack on the Italian fleet at Taranto in 1940 had suggested to the Japanese that such an assault was possible. The reasons leading to the attack, and the events of the attack itself, have been detailed innumerable times. For the purposes of this post, however, the critical thing is that the new Japanese doctrine worked well. The 353 aircraft launched from the decks of Kido Butai savaged not only the fleet at anchor in Pearl, but also the aircraft and equipment ashore. It was perhaps the easiest possible target: a naval base taken by surprise, with ships at anchor, boilers dark. Having said that, even such an overwhelming assault failed to destroy critical parts of the base: the American submarine pens, the fuel oil farm, and, most critically, the American aircraft carriers. Such was the inefficiency of air attack in 1941.

It was, nonetheless, a spectacular success for the Japanese. They had demonstrated to themselves and to the world the effectiveness of concentrated naval airpower. Kido Butai would roam the Pacific over the next six months, hammering target after target and ranging as far as Sri Lanka in the Indian Ocean and Australia in the southern Pacific. But the Americans were fast learners and in this new naval doctrine loomed the seeds of Japanese defeat. If the benefit lay not in who could amass an extra ship or two, but an extra fleet or two, then the Americans had a decisive advantage, not only in the production of carriers and planes (24 American vs. 16 Japanese during WWII) or planes (over 300,000 for the U.S. vs. 75,000 for the Japanese) but in the industrialization of pilot training (several hundred thousand vs. 15-20,000). By 1945, the “Murderer’s Row” of the American 3rd and 5th Fleets, with 8-10 carriers and over 500 planes, roamed the Pacific, hammering the Japanese as Pearl Harbor had been hammered. The six carriers of Kido Butai did not live to see that day.

|

“The Legend of John Brown” by Jacob Lawrence

Editor’s note: Caleb McDaniel, who many of you (at least those of you familiar with internet traditions) may remember from modeforcaleb, joins us today for a guest post. Thanks, Caleb, for taking the time to do this. We really appreciate it.

One-hundred-and-forty-nine years ago today, the state of Virginia hung the militant abolitionist and Kansas Free State warrior, John Brown.

A month and a half earlier, Brown had led a band of twenty-two men, including three of his sons, in a daring–and disastrous–raid on the federal armory in Harpers Ferry in western Virginia, a raid intended as a direct strike on the institution of slavery within the South itself. Captured on October 18 and quickly tried by the state, a wounded Brown spent November in a jail cell in Charlestown, Virginia. Then, on December 2, he was escorted from his jail cell to the gallows. As he left the prison, he handed a note to his jailor predicting that more lives–many more–would be lost before slavery died: “I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty, land: will never be purged away; but with Blood.” Barely one year later, South Carolina seceded from the Union, initiating a sequence of events that led to the American Civil War.

[Editor’s note: zunguzungu, long-time commenter and friend of the blog, has stepped up with a guest post today. Thanks for this. We really appreciate it.]

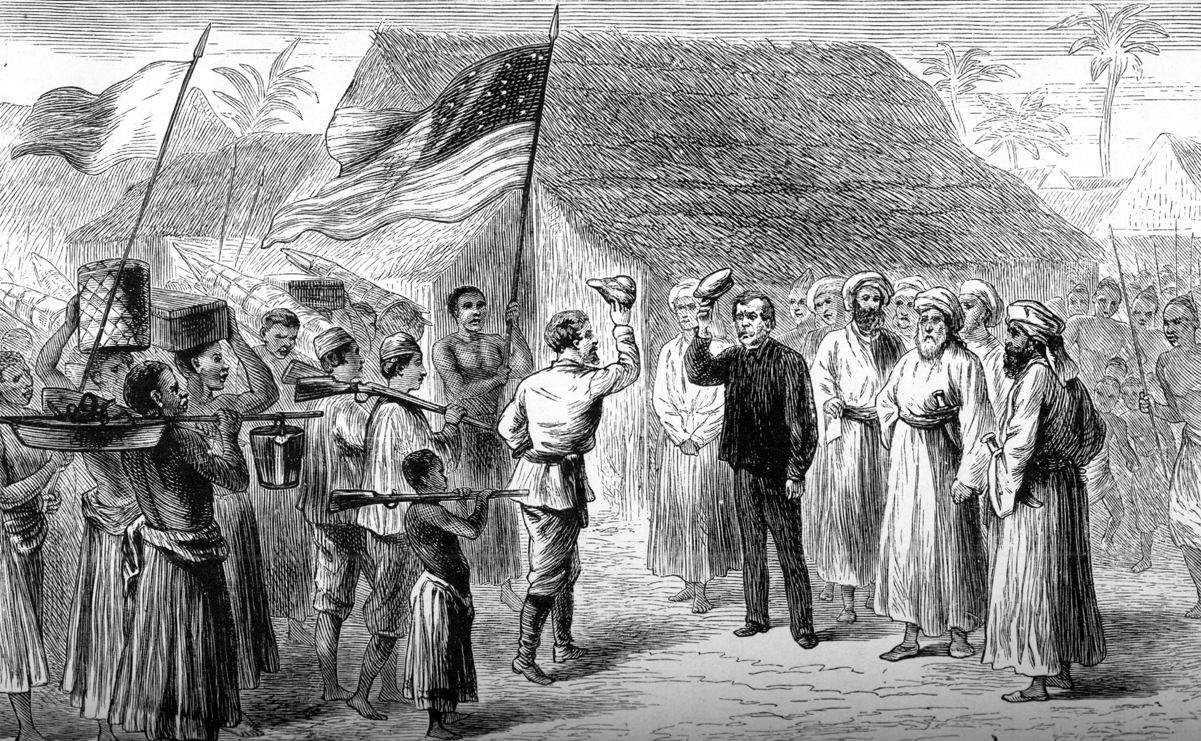

Henry Morton Stanley pretended to have written something in his diary on November 23rd, 1871. Perhaps he did, though the pages in his diary are torn out, so we can’t know for sure. The event he claimed to have recorded — but probably didn’t — also probably didn’t happen, or at least not the way it’s usually “remembered.” He most likely didn’t say “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” on meeting the older doctor (Tim Jeal says so in his new biography), and he didn’t even meet him in the jungle at all. He met him in a town, as this image from How I Found Livingstone illustrates:

As Claire Pettitt put it in her excellent Dr Livingstone I Presume?: Missionaries, Journalists, Explorers, and Empire, it’s a phrase we remember without really remembering why, and pages torn out of a diary are an apt figure for the ways that forgetting what really happened have been the first step in making the event meaningful. For example, while Welsh-born Stanley would eventually give up the pretense of being from Missouri, he was, at the time, widely recognized as an American figure allowing the event to be contemporaneously interpreted by reference to an Anglo-American partnership that was going through a rough patch. As Pettitt illustrates, news of his discovery literally competed for column space with news of the negotiations in Geneva where the issue of British support for the Confederacy was being officially resolved, and this was symptomatic more broadly: Stanley’s narrative of the American finding a revered English abolitionist (though he was actually Scottish) in the jungles of Africa did a similar kind of work as the diplomats in Geneva in re-cementing a sense of Anglo-American moral identification. Read the rest of this entry »

[Lori Clune returns for another guest post. Thanks, Lori, for freaking me out.]

On this day in 1950, the Washington Daily News ran a story describing “the crazy attempted assassination” of President Harry S. Truman. On November 1st – while the president took a nap in his underwear on an unseasonably warm autumn afternoon – two Puerto Rican nationalists tried to assassinate Truman in hopes of sparking a Puerto Rican independence movement. Only a locked screen door and security guards stood between Truman and the assassins. Both men, Griselo Torresola and Oscar Collazo, were shot before they could get inside the house. Torresola, suffering a head wound, died instantly. Collazo, tried, convicted, and sentenced to death, was saved when Truman commuted his sentence to life. President Carter ordered Collazo’s early release in 1979, and he died in Puerto Rico in 1994. He did not live to see a significant Puerto Rican independence movement.

The shooting, as detailed by John Bainbridge, Jr. and Stephen Hunter in American Gunfight, lasted nearly a minute with gunfire exchanged between the assailants and White House policemen and Secret Service agents. Three guards were wounded and a fourth was killed. None of the first family were harmed.

The gunfight actually didn’t take place at the White House. From 1948 to 1952, the White House underwent a $5.4 million renovation. Not known for living opulently, Truman saw his daughter’s piano leg break through the floor and into the room below before he agreed to replace the rotting wood with a steel skeleton structure. So, Harry, Bess, and Margaret moved across the street to Blair House for the duration. As a result of the assassination attempt, Truman was no longer allowed to walk from Blair House to the White House, causing him to state, “It’s hell to be President.”

Meanwhile, Puerto Rico remained a commonwealth. Just prior to the assassination attempt a three-day revolt – the Jayuya Uprising – had erupted in Puerto Rico and failed. The nationalists wanted to remove U.S. control; what they got was martial law. The ghost of Torresola rose on March 1, 1954, when four Puerto Rican nationalists entered the visitor’s gallery of the House of Representatives and shot into a crowd of congressmen. President Eisenhower wrote very nice sorry-you-got-shot-in-the-Capitol letters to each of the five wounded congressman. He also commuted the attackers’ death sentences to life. But Puerto Rico remained a commonwealth.

Throughout the Eisenhower years the country debated the merits of adding another star to the flag. Should we make Puerto Rico a state? How about Alaska? Hawaii? By 1959, a consensus emerged, though Eisenhower remained opposed to Alaskan statehood until the very end, vowing to veto statehood for “that outpost.” What if? Puerto Rico and Hawaii as the 49th and 50th states?

[Chuck Walker has decided to squander some of his precious time today by posting on the 1746 Lima earthquake. Chuck’s extraordinary new book, on the same subject, can be found here. Thanks, Chuck, for agreeing to join us.]

On this day in 1746 a massive earthquake walloped Lima, Peru, the center of Spain’s holdings in South America. Tumbling adobe walls, ornate facades, and roofs smothered hundreds of people and the death toll reached the thousands by the next day. About ten percent of this city of 50,000 died in the catastrophe. The earthquake captured the imagination of the world, inspired Lima’s leaders to try to rethink the city, and unified the city’s population–in opposition to these rebuilding plans. With constant aftershocks and horrific discoveries of the dead and wounded, despair as well as thirst and hunger set in quickly. Life was miserable for a long time. Limeños took to the street in countless religious processions, bringing out the relics of “their” saints such as Saint Rose of Lima or San Francisco de Solano. People took refuge in plazas, gardens, and the areas just outside of the walled city.

Things were worse in the port city of Callao, ten miles to the west of Lima. Half an hour after the earthquake, a tsunami crushed the port, killing virtually all of its 7,000 inhabitants. Some survivors had been inland or in Lima while a few made it to the top of the port’s bastions and rode it out. Several washed up alive at beaches to the south, telling their miracle stories to all who would listen. One woman had floated on a painting of her favorite saint. Merchants in Lima who kept houses, shops, and warehouses in Callao claimed that when they arrived the next morning they could not find the site of their property—no landmarks remained. The water not only ravaged people, animals, and structures but also swallowed up the city’s records. For years people petitioned to the courts about their identity or property, unable to show their papers in the well-documented Spanish colonial world.

The earthquake/tsunami takes us into areas where historians cannot normally venture—we have descriptions of where people were sleeping and life (and death) in cloistered convents. It also serves as an entryway into the mental world of the era, as people displayed their fears and priorities. Some worried about recovering their property and others about rebuilding social hierarchies; some more subversive-minded members of the lower classes saw it as an opportunity. Everyone suffered, however, with the loss of life and the misery of the following months.

The Viceroy and his inner circle did a remarkable job of stemming panic, assuring water and food supplies, and rebuilding the city. José Manso de Velasco, who would be titled for his efforts the Count of Superunda (“Over the Waves”), quickly gathered his advisors, surveyed the city on horseback, and took measures to rebuild water canals and find food from nearby towns and beached ships in Callao. His social control measures contained an ugly racialized side as authorities and elites fretted about slaves liberating themselves, maroons raiding the city, and free blacks dedicating themselves to crime. Martial law apparently stopped a crime wave although stories circulated about people tearing off jewelry from the dead or dying. People lined up at nearby beaches to collect washed up goods and many died when ransacking tottering houses—either from the caved in structures or angry crowds.

The viceroy managed to assure food, water and relative calm. The Bush administration would envy his success or at least his public relations coup. In part it reflected Manos de Velasco’s experience as a city builder (he had done this in Chile where he was stationed previously) and his relative hands-on approach. But absolutist authorities were good at emergency relief; in some ways, this is what they did. They couldn’t allow the people to go hungry (or to eat cake) and so Manso de Velasco requisitioned workers and flour and banned profiteering. People of all castes and classes lauded him for his willingness to sleep in the central Plaza.

Yet the Viceroy’s plans went far beyond immediate efforts in public safety. He and his advisors sought to change the city in classic eighteenth-century fashion. After deciding not to move it elsewhere (in part because they so fretted over the thought of maroons taking over the remains of the former viceregal capital), they sketched out a city with wider streets, lower buildings, and less “shady” areas. They wanted people, air, and commodities to circulate with greater ease, with all movement ultimately leading towards the Viceregal Plaza in the main square. Think of a frugal version ofVersailles. His plan, quite brilliant in theory, failed miserably. It managed to bring almost all Peruvians together, but in opposition. The upper classes rejected limiting their rebuilt houses to one story and tearing down some of their heavy facades, status symbols that proved deadly in earthquakes. They claimed he didn’t have the right and fought him for years. The Church saw the plan to impede them from rebuilding some churches, convents, and monasteries (there were an astounding 64 churches in Lima at the time) as a dangerous step towards secularization. They stressed their role in aiding the wounded and destitute and reasoned that since the earthquake was a sign of God’s wrath, did it make sense to anger him even more?

The lower classes did not like the plan. Afro-Peruvians resisted the social control campaigns aimed squarely at them and Indians (surprise, surprise) did not flock to the city to volunteer for rebuilding efforts. In fact, blacks and Indians organized a conspiracy that rocked the city less than four years after the earthquake and spread into a nearby Andean region, Huarochirí. Authorities arrested conspiracy leaders when a priest passed information about it that he had learned in confession. They executed six conspirators, displaying their heads for months. The rebels planned to flood the central Plaza and then kill Spaniards when they fled their homes. One participant proposed that any rebel who killed a Spaniard would assume his political position. While nipped in the bud in Lima, the uprising spread in the nearby Andean region of Huarochirí. After rebels took several towns and imprisoned and even killed local authorities, officials in Lima fretted that they would take the city, link with a messianic movement in the jungle, and even ally with the pernicious English. A Lima battalion, however, captured and executed the leaders. Manso de Velasco proved highly capable in efforts immediately after the earthquake. He was much less successful in using the catastrophe to create a new Lima.

There is an old, perhaps dead, journalism standard that third-world disasters merit little if any attention. Stories on “earthquake in South America kills hundreds” should accordingly receive an inch or two on page 19, at best. Did international savants and writers overlook Lima’s earthquake-tsunami? Not at all. Earthquakes fascinated the erudite in Europe and what became the United States. They debated their causes in this pre-plate tectonics era, contributing to trans-Atlantic polemics about whether the Americas was a younger, more humid, and inferior continent. The Comte de Buffon and Thomas Jefferson feuded on this question. Accounts of earthquakes also interested some Englishmen with imperial yearnings, who saw them as an opportunity to take over from the “weak” Spanish. This interest increased greatly in 1755 when the Lisbon earthquake took place and became an obligatory topic for virtually all European intellectuals. Lima plays a role alongside Lisbon in Voltaire’s Candide. One account of the Lima earthquake was published in Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Dutch, and English, including a lovely edition by Benjamin Franklin (Philadelphia, 1749). The 1746 earthquake was by no means an overlooked and distant “third world” disaster.

I was in Lima for the destructive August 15, 2007 earthquake and confirmed that the Peruvian state’s response to earthquakes has changed over the centuries, not necessarily for the better. President Alan García’s efforts were more Bush than Manso de Velasco. While making impassioned speeches and taking the obligatory tour of the ruins in Pisco, the epicenter south of Lima, his government was unable to guarantee food, water, and shelter. And while international organizations and governments promised relief, the people of Pisco still live in makeshift tents and most of the city remains in shambles. The May 2008 China earthquake pushed Peru out of the press. Perhaps Peru needs a viceroy or at least a more committed and efficient leader; the world could always use a Voltaire and a Benjamin Franklin.

Recent comments